Hope for the cynic

by Serena Chen

Sometimes, when the noise of every day life becomes a bit too much, I like to step back and imagine myself observing the world as if I were a historian from the not-too-distant future. What would they say about this strange time that we live in? What patterns would they see that we would miss?

When I look at the reactionary movements on the right, the burnout and despair on the left, the new language and culture of irony adopted by seemingly everyone — it really does feel like we’re living in an age of cynicism.

Over the years, cynicism has become a cultural shorthand for intelligence. If you want to signal that you are a well-read, independent mind, the quickest way to do that is to espouse cynicism. Repeat the right ironic phrases and you will be deemed a free-thinker. (How ironic.)

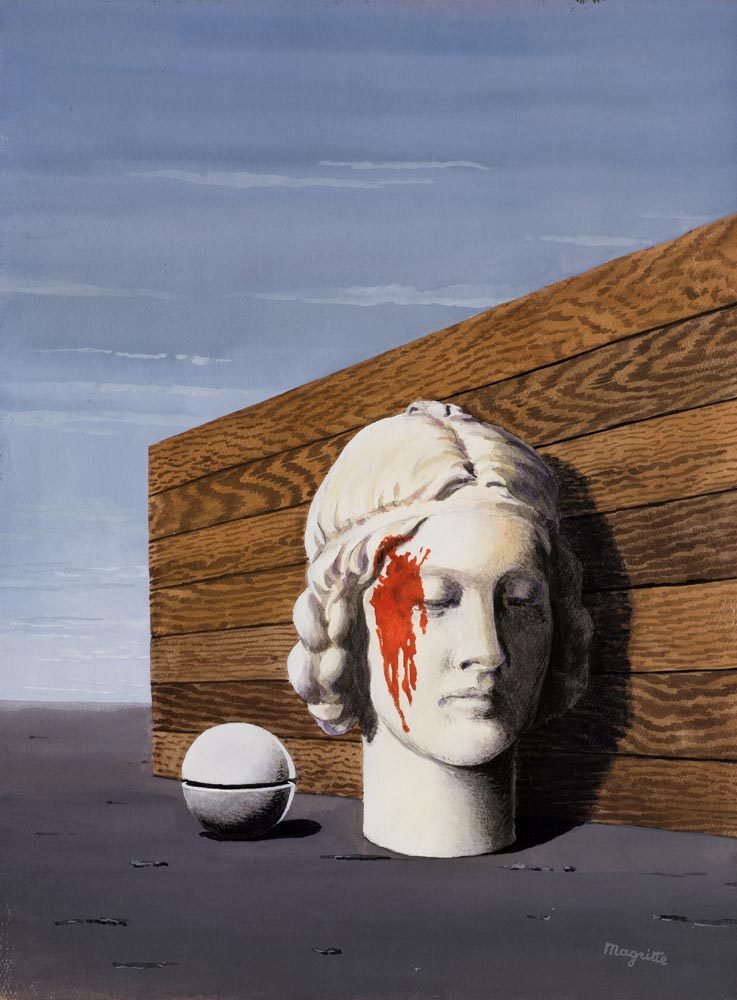

Our stories, art, and culture have moved down the same path. Videogames and films must be increasingly violent and sadistic to cultivate an air of “realism”. Our television shows feature “anti-heroes”, painting themselves as nuanced and multi-faceted when in practice it becomes an excuse to indulge in violence and assholery without having to genuinely dissect these actions. And on many parts of the internet, the name of the game is to never be caught believing in what you say. “Trolling” is a thing. Everything is ironic. Everything is a troll. Everything is a joke.

Lately I’ve been reading a lot about the reactionary right: their aesthetics, their talking points, their beliefs. There’s a certain inevitability to it all, a sort of fate that you cannot escape, a hopelessness, a powerlessness. The idea that every part of your life, and who you are as a human being, is wholly determined by things you cannot(Without a lot of effort) change like genetics, skull shapes, race, sex, and so on. These groups call themselves “race realists”, “gender critical”; adopting the language of the intelligensia, much like how pop culture adopts the same surface-level signifiers without ever interrogating them far enough to say something of substance.

One of the most enlightening explainers I’ve seen to date is Contrapoint’s video on incels. In it, she describes the aesthetics, beliefs and ultimately the motivations of this strangely doom-obsessed community, and distilled it down to what it was: a death cult. The idea that life is preordained by social structures, so much that your current circumstances are eternal, so you might as well LDAR (Lie Down And Rot).

There’s a magnetism about this fatalistic way of thinking, and I’d be remiss if I didn’t admit that I can feel drawn to it too. No, not the weird obsession with skulls, but the idea that everything bad is true, and everything good is a lie. If someone compliments me, a small voice in the back of my head tells me they’re lying to make me feel better. The more harshly someone puts me down, the more I suspect it just might be true. There’s this undercurrent of distrust in the world around us; the suspicion that we’re all suckers at the end of the day, waiting to be duped and taken advantage of by those who have more power than us.

This is not a characteristic unique to right-wing reactionary groups. This is something I see everywhere.

It’s a manifestation of our inner fear and cowardice. While once cynicism and irony was a counter-culture way in which one could critique the mainstream, now it is a pop-cultural mainstay. It’s a way to insulate ourselves with the very criticisms that might be hurled against us. “Wearing our faults like armour”

is empowering when those “faults” are not really faults (like your sex, your ethnicity, your love of trashy pop music). But this “wearing your faults as armour” becomes regressive when we pridefully display the faults that harm others, that harm ourselves, that we wholly have the power to change.

And that’s both the power and the problem with cynicism and irony — it is impervious to criticism, while brandishing itself as brave, rebellious, and intellectually stimulating. “Look at how I’ve started this conversation,” it says, shutting the conversation down.

Cynicism tells us that the world we know, right now, is eternal and forever. Cynicism says this is just how things are and have always been, and if you don’t like it then you might as well just Lie Down And Rot.

Cynicism is the dream killer. Cynicism stops progress in its tracks. Cynicism denies us a better world.

Sometimes despair or grimness calcifies out of honest idealism, disappointed again and again, out of pain at the atrocities unfolding. Rebecca Solnit, Hope in the Dark

There’s a moment in Netflix’s recent documentary, Knock Down The House, where now US Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez displays brief moment of self-doubt and vulnerability.

“I’m aware of the cynicism that can come, when people believe in something, put their hearts and souls into something… and then it doesn’t work out,” she says, slowly, deliberately, with such apprehension in stark contrast to how she usually speaks. “I just don’t want to disappoint anyone.”

The burnout that comes with investing energy in any political activity (or even just political belief) is well-known. There’s a reason why no one likes politics: it’s tiring. As Rebecca Solnit points out, things that make effective activism are short, simple, urgent. Something that can be chanted at a protest, tweeted and retweeted in the thousands. But things that reflect change — real change — are often long, complex, and spans decades. If we expect instant gratification like we do everywhere else in our modern lives, we will be disappointed, again and again.

It is easier to imagine the end of the world than it is to imagine how a world might change.

In some ways, the world has ended, and started again, multiple times over already. I remember those hours right after reports of the shooting in Christchurch reverberated across the country. I remember walking to the vigil in Wellington. Busloads, full of people, flooded the streets. People spilled out of the footpath and onto the roads. People just kept arriving. I had never seen so many people in Wellington before.

In the days after the terrorist attack, everything felt heightened — more local, more immediate, more real. It was strange — I had never felt more connected to the place I lived in. Suddenly I felt the full weight of responsibility of what it meant to be part of a community. The responsibility that we all felt in those dark days, to shower each other, especially our Muslim whanau, with as much love and solidarity so that no violence could ever touch us again. As if love could protect us from bullets.

Three months on, I worry that we’re losing that sense of community. I worry that we’re throwing away the tiny speck of hope and connection that we felt in the midst of such despair. Buried in the aftermath of the horror, was a gift. The reminder that no one is truly alone in this world, that we are all capable of love and connection and faith in the fellow stranger.

Things are pretty dark right now. And in a dark time, optimism feels… stupid, to be honest. But I think we all need to remind ourselves: being optimistic is not about pretending things are okay. Things are not okay. Things feel as far away from okay as they have been in a while. Things are fucked.

Being optimistic is looking at just how fucked everything is, rolling up your sleeves, and saying, “let’s get to work.”

If I could sum up the most important thing I’ve learned in my adult life, it’s that the structures that govern our lives and ourselves are often unspoken and invisible. The most important thing I’ve learned is that everything — everything — is made up. By people who barely know what they’re doing. Adulthood is just childhood with a brave face. There is no right way that we’re “meant” to do anything.

This can be really scary, because no one really knows what they’re doing. But it can also be empowering. You don’t have to do things a certain way. Like how, when we first came to New Zealand, mum would negotiate the price of everything. People would look at her weird (including me, because internalised racism), but hey, sometimes it would work and she would get a better price. You don’t know if you never try.

As we are born into this world, and as we move from school to work, from industries to communities, we enter already-made environments that come with their own sets of rules and “the way we do things”. We tend to forget that these rules weren’t always the case. Someone made them up. If something doesn’t work, you can change it. You can unmake and remake these spaces in your own vision.

It sounds impossible — and it is, by yourself. But together, it can be alarmingly easy. Together, things are impossible and then suddenly they’re not.

In our increasingly individualised world, it’s getting harder and harder to even imagine true collective action. We see everyone as protagonists of our own stories, individuals with complex feelings and beliefs and goals. It’s hard to imagine bringing together so many unique parts.

But we forget that history is a dance, a school production, a team sport. An intricate weave of interconnected actors, coming together on a stage, in the field, in the world.

We forget that nothing ever ends. It’s not about destroying evil for some happily ever after. It’s about continually building the good.

We cannot eliminate all devastation for all time, but we can reduce it, outlaw it, undermine its sources and foundations: these are victories. A better world, yes; a perfect world, never. Rebecca Solnit, Hope in the Dark

On the other extreme, there is no easier way to sink into cynicism than to hold up the mantle of perfection. Ideological purity is accidental selfishness masquerading as deliberate selflessness. It is choosing an imagined, puritan paradise in a fictional future, over any real, concrete steps forward in the now.

This is not to say that ideological purity is without its use. It is a north star, a guiding principle by which to navigate to. It is there to inspire us, to connect us, to rally us. Celebrating the increments is not a reason to stop — it is a reason to keep going.

I mean, I get it. I feel the overwhelming disillusionment that comes when you lose more than half of everything you’ve fought so hard to gain. Yet still, you’ve gained.

Here’s something harder to think about than utopia or apocalypse: continuing. We need all be reminded that the future is not set, not ever set; which is scary, terrifying, and inherently hopeful.

Everyone that terrifies you is sixty-five percent water.

Every system that binds you was once a figment of someone’s imagination. Yes, sometimes it feels like we’re shouting into an endless void, and you don’t have a voice when you’re alone — but you’re not alone. Contrary to how it feels, we are not alone.

A year ago, if you had asked me to imagine what success would look like, I might’ve imagined a handful of heroes, with power and influence, pulling the tides of history towards justice. Now, I imagine millions of people. Mostly going about their everyday lives, but sometimes, a few thousand will band together, call their representatives, make sure their neighbours are enrolled to vote. And then they go back to their lives. This will not be their life story. Direct action becomes another thing we just do — like laundry, like taking care of the plants.

Knowing that I am small and insignificant is a little sad. Knowing that everyone is small and insignificant is powerful. There are no heroes — just everyday people, trying their best. All of history’s greatest achievements and worst tragedies were performed by people, so small and insignificant in the cosmic scale, just like you or I.

Lately I’ve noticed myself slip further and further into the dark and warm embrace of cynicism. Oh, how much easier it is to make a smart-ass comment about how broken the world is, instead of banding together and doing something, anything, to fix even just a little part of it.

Someone wise once told me that the easiest way to combat the feeling of powerlessness is to do something. To tear our attention away from the endless projectile vomit that is the news and start with yourself, your rag-tag group of friends who care, and the people in your own communities.■

The trouble is that we have a bad habit, encouraged by pedants and sophisticates, of considering happiness as something rather stupid. Only pain is intellectual, only evil interesting. This is the treason of the artist; a refusal to admit the banality of evil and the terrible boredom of pain. Ursula LeGuin, The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas

Related and recommended texts

- Hope in the Dark, by Rebecca Solnit

- The Most Radical and Rebellious Choice You Can Make Is to Be Optimistic, by Guillermo del Toro

- The Age of Cynicism, by Mohammed Fairouz

- Knock Down The House, by Rachel Lears

This post was originally published in my newsletter.